Writing about cake would be a good idea for just about anyone. It's not, however, for a low-carber.

Yes, I'm a low-carb eater. This means I don't eat bread or pasta; I eschew flour and sugar; I shun starches and sweets. I'm supposed to, anyway. It's for my health.

A few years ago, I was trying to lose a few pounds. I'd suffered from insomnia since the birth of my daughter, and I had carpal tunnel and a host of aches. I went on Atkins, and I suddenly began to sleep without aids and found I no longer needed anti-inflammatory drugs, either. I no longer needed to wear wrist guards—hulking hand contraptions—to bed. In three weeks, I was near goal weight; in a few months, I was off my antidepressants and sleeping pills.

Enter the Cake Thesis.

Perhaps my decision to explore the moist white underbelly of the cake world was a bit misguided (read: stupid). It wouldn't be so bad if I had stopped at cake. But once that oven door opened, the hot dog roll began to go down with the hot dog, the hamburger bun starting going down with the hamburger. Instead of delicious sauteed zucchini going down with the spaghetti sauce, pasta goes down.

Consequently, pain goes up.

I have been back on track for three days now, and I am slowly recovering. Cake for work (and birthday—I mean, c'mon) will be my only high-carb allowance.

On a forum, women friends recently discussed why we do this to ourselves, knowing it causes a world of problems. How can we see something that causes bloating and confusion and insomnia and swelling and inflammation and pain as a reward?

A frank and thorough writer cannot simply explore the light side; cake has a dark side, too (a gooey, rich, chocolate side, perhaps, but it's dark).

In a few weeks, I will be talking to some mental and physical health experts at Hopkins about the sweet tooth and the nature of food addiction. Perhaps I will learn to develop a more professional relationship with my subject

Because when it comes to sweets—especially cake—I have an inability to think beyond the moment to its consequences. It's all about instant gratification and momentary pleasure. There's rarely a hint of critical thought when I am faced with cake. Cake. Hmmm. Here you are. I will eat you.

The only things that run through my mind have to do with strategy. I am a cake soldier on the front lines competing with other cake soldiers. In seconds, I must figure out how to get the corner piece, how to eat it without looking like a crazy homeless person, how to get a second hunk, how to get that blop of frosting—that one, over there, yes, yes, yes.

28 September 2005

25 September 2005

Cake is God

Cake is everywhere.

It arrived at my daughter's morning soccer match, when a woman announced she had to leave early to bake a boiled milk cake. You're writing a book on cake, and you've never heard of a boiled milk cake? her eyes seemed to say. "What about a 1-2-3-4 cake?" She was testing me. This is obviously a pound cake, named for butter, sugar, flour, and eggs. The milk never counts, even though that's what makes it so moist.

Cake was at the Baltimore Book Fair in the guise of a moon bounce. The candles wiggle a bit when the kids are hopping inside, working off that white sugar buzz from all that fried dough their moms used to bribe them to just shut up during the poetry readings that were for their own good.

The cake contest I entered last week was for a birthday cake in honor of the Fair's 100th birthday. (Had I known, I'd have made my entry more festive.) The judging is today at 4:00, and it's hosted by Duff Goldman, the subject of my desires.

Cake happened while I slept last night, too. At midnight, Theater Project hosted one of the High Zero (an experimental music) festival events: Amplified Cake. Actually, it's called Cake Mix, and it features, "[a]n amplified cake [getting] slowly eaten while [the room plays] Baltimore club beats from within. Get yer freak on for sweets."

Forget the illogical syllogism. Cake really is everywhere, and it really is God.

It arrived at my daughter's morning soccer match, when a woman announced she had to leave early to bake a boiled milk cake. You're writing a book on cake, and you've never heard of a boiled milk cake? her eyes seemed to say. "What about a 1-2-3-4 cake?" She was testing me. This is obviously a pound cake, named for butter, sugar, flour, and eggs. The milk never counts, even though that's what makes it so moist.

Cake was at the Baltimore Book Fair in the guise of a moon bounce. The candles wiggle a bit when the kids are hopping inside, working off that white sugar buzz from all that fried dough their moms used to bribe them to just shut up during the poetry readings that were for their own good.

The cake contest I entered last week was for a birthday cake in honor of the Fair's 100th birthday. (Had I known, I'd have made my entry more festive.) The judging is today at 4:00, and it's hosted by Duff Goldman, the subject of my desires.

Cake happened while I slept last night, too. At midnight, Theater Project hosted one of the High Zero (an experimental music) festival events: Amplified Cake. Actually, it's called Cake Mix, and it features, "[a]n amplified cake [getting] slowly eaten while [the room plays] Baltimore club beats from within. Get yer freak on for sweets."

Forget the illogical syllogism. Cake really is everywhere, and it really is God.

22 September 2005

Magic

I described to my good friend, Paul, my idea for a cake story, a chapter in my book in which I visit various "cake factories," from the upscale, extravagant cake production companies like Charm City Cakes, all the way down to the little snack cake plants.

I explained that I wanted to go behind the scenes of the cake-making process without actually demystifying it.

Paul, a genius in many ways, understood perfectly. He called me the Penn and Teller of cake.

I explained that I wanted to go behind the scenes of the cake-making process without actually demystifying it.

Paul, a genius in many ways, understood perfectly. He called me the Penn and Teller of cake.

20 September 2005

cake fantasy

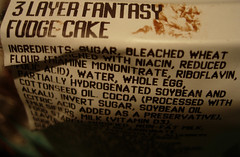

No. The fantasy is not, trust me, enriched, bleached wheat flour and hydrogenated oils. It is not emulsifiers and leaveners, preservatives and colors and flavors.

The fantasy is not that you can smear it on the bodies of the ones you love and remove it with your tongue.

The fantasy, my friends, is being able to eat the 3 layer fantasy fudge cake and look good naked.

The fantasy is not that you can smear it on the bodies of the ones you love and remove it with your tongue.

The fantasy, my friends, is being able to eat the 3 layer fantasy fudge cake and look good naked.

3 Layer Fantasy Fudge Cake

Last night, as an apology for the registrar having overloading my honors writing class, the coordinator of the honors program dropped off a 3 Layer Fantasy Fudge Cake, a silver cake server, some foam plates, and a stack of elegant napkins. Most of the class sat there, meekly, refusing to admit they wanted to devour the cake at that moment, naked and in private.

Even when I discovered and announced that it tasted like crushed Hostess Ho-Hos or Ring Dings, the cream replaced with wet, delicious fudge, most of them just sat there. One had the effrontery to proclaim that "it was too early for cake." Too early? For cake? The perfect breakfast, brunch, lunch, dinner, dessert, or midnight snack? That cake?

A few of the less inhibited (read true) rose without delay. I recognized a kindred in one of them, Auriane, whose eyes glazed over with a rapture much like my own, if twenty years younger.

When I lectured, cake crumbs flew willy nilly from my lips. I kept looking down at it until one student suggested I replace its plastic lid. I told my class that I just wanted to roll in it.

Perhaps I reveal too much of myself.

Despite its dark deliciousity, despite its fudgy freshness, it is not, thankfully, white sheet cake. With white, buttercream frosting. I brought the remainder—about eight or ten three-high slices, covered in thick shavings of chocolate—home for my husband and daughter. The cake did not call me, wake me in the middle of the night, begging for my lips. I slept soundly and sent the cake off to my husband's office this morning, just in case it decided to speak this evening.

Even when I discovered and announced that it tasted like crushed Hostess Ho-Hos or Ring Dings, the cream replaced with wet, delicious fudge, most of them just sat there. One had the effrontery to proclaim that "it was too early for cake." Too early? For cake? The perfect breakfast, brunch, lunch, dinner, dessert, or midnight snack? That cake?

A few of the less inhibited (read true) rose without delay. I recognized a kindred in one of them, Auriane, whose eyes glazed over with a rapture much like my own, if twenty years younger.

When I lectured, cake crumbs flew willy nilly from my lips. I kept looking down at it until one student suggested I replace its plastic lid. I told my class that I just wanted to roll in it.

Perhaps I reveal too much of myself.

Despite its dark deliciousity, despite its fudgy freshness, it is not, thankfully, white sheet cake. With white, buttercream frosting. I brought the remainder—about eight or ten three-high slices, covered in thick shavings of chocolate—home for my husband and daughter. The cake did not call me, wake me in the middle of the night, begging for my lips. I slept soundly and sent the cake off to my husband's office this morning, just in case it decided to speak this evening.

18 September 2005

Pounds Cake

At five o’clock, I have no idea what I am making for dinner, but I am about to put a pound cake in the oven. I’m a sloppy baker. I can break eggs with one hand (a skill that not only looks impressive but is useful, as my other hand is often busy cleaning up the things I’ve knocked over with the egg hand), but I always wind up with batter on my shoes. Today, I’m wearing a pair of black, toeless slides, and the drop lands between my first and big toes.

The recipe on the bottle of flavoring calls for shortening and margarine; I’ve already altered it by using all butter. (“It’ll be richer,” Susan Staehling told me earlier, her tone almost a warning.) Everything else—the six eggs, the three cups each of flour and sugar, and the cup of sweet milk—is by the book. (Sweet milk is whole milk. Susan once called the Superior company to check, and they told her the recipe was from a time when “women milked their own cows.”) The flavoring is added last, to the milk. It smells like an alcoholic version of candy corn—delicious. I am starting to regret my decision to make this cake. Maybe it won’t be as resistible as I expect.

The last thing I do is soak one of those Magi-Cake strips and pin it to the tube pan. (I probably shouldn’t reveal that I looked up pictures of tube pans on the Internet to make sure I was using the correct thing. I had always called them Bundt pans, not realizing Bundt is a brand.)

My daughter comes in from tree climbing and wants to know if it’s pound cake she smells in the oven. She spies the mixer attachment on a plate, and goes directly there to eat whatever batter is left. She assumes it is for her and doesn’t ask if she can eat it, though it is near dinner time. Her eyes roll back in her head, our household code for yummy.

And when it’s out of the oven, I can’t resist peeling off a piece where the cake has split, despite the Magi-Cake strip, though it is mighty flat. I am too impatient for a complete cool down and turn the cake over onto the lid of a plastic storage container. It’s far too pretty for plastic. I fish out my glass cake plate with the sterling silver base and reposition the fluted pound cake atop it, and then I take its portrait: my first cake as a—a cake book writer. My first pound cake. I pose it with a slice removed. I shoot the slice on a plate.

My neighbor, Ann, the cake decorator, is first on the tryout list. She looks at me, wide-eyed. “It’s so moist!” She says she’s tried dozens of recipes for pound cake and always comes out with cakes that are dry on the inside and crusty on the outside. I tell her about the butter-vanilla-nut extract from Cake Cottage, and she reaches behind some things to find her own bottle; she doesn’t remember seeing a cake recipe on it. I complain that the cake tastes a little artificial. Is it because I know the extract is imitation? Would real walnut and pure vanilla have made a difference? “Tastes good to me,” says Ann’s husband, Jim, in typical husband fashion.

Back at home, my own spouse declares the cake as moist and delicious as any other. But my daughter thinks it’s more desert than dessert and begs for ice cream. I want to tell her that she’s right, that cake without frosting might as well be bread. But I am too busy chewing a piece, nodding, my heart starting to beat just a little faster.

* * * *

According to the authorities on the subject—Rose Levy Beranbaum, author of The Cake Bible, and Bruce Healy, co-author of The Art of the Cake—I have made my pound cake all wrong. I said I had made this cake “by the book” with the exception of my use of butter, but I failed to mention that I softened it in the microwave. Berenbaum may not have a problem with that; her pound cakes, dubbed “perfect,” call for softened butter. But her recipes call for flour first, and she uses baking powder and far less milk. Healy would find neither recipe very French. His traditional quatres-quarts (named four-fourths because the original recipe called for equal parts flour, butter, sugar, and eggs), calls for everything at a specific temperature; the eggs, for instance, are at room temperature, while the butter is sliced and then creamed while still cold (unless your kitchen is cool), the superfine sugar chilled in the fridge. These two don’t even agree on what to use as a cake tester: Berenbaum suggests a wooden toothpick; Healy opts for a knife—a toothpick or cake tester is under-endowed with sufficient surface area to which wet batter can cling.

If nothing else, I am a person who can follow directions, so I use this skill to sponsor my own Pound Cake Bake Off, much to the delight of family and my many neighbors, all of whom seem to exhibit oodles more self-control than I.

The pound cake has been around since at least the 1700s. In 1796, Amelia Simmons (whose by-line includes “an American Orphan”) published this country’s first cookbook, entitled, American Cookery, or The Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables and The Best Modes of Making Pastes, Puffs, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from Imperial Plumb to Plain Cake, Adapted to This Country and All Grades of Life. In an edition published by William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1965, some of the original grammar is cleaned up a bit, though the author of the Foreword assures readers, “Enough errors remain to leave the proper flavor of the original. (Also note that the printer’s long f symbol of the time was used where we now use the curved s.) Her recipe for Pound Cake calls for:

In more than two hundred years, the recipe has not changed much. Though we don’t measure in gills (about five ounces) or use rose water or, alas, brandy, a pound cake is a pound cake.

*****

Bruce Healy’s Quatre Quarts is in the oven. Despite my determination, my cautious preparedness, I am still a slob. The countertop has a light dusting of flour, egg drops have dried there, too, and everything near the stove is covered with a greasy film from a morning spent attempting to clarify my own butter. Both The Cake Bible and The Art of the Cake recommend clarified butter for the greasing of the cake pan; otherwise, the cake is likely to stick to the milk solids in regular butter. In economic terms, this means turning two sticks into one. I boiled the butter, skimmed the foam from the top, and strained the solids. Several times. Eventually, I wound up with a delightfully clear butter with which to coat the loaf pan (to keep the cake from sticking). I never got to use it. My loaf pans have a non-stick surface too slick to hold melted butter; it runs down the sides and pools on the bottom. I put the clarified butter in the fridge and rubbed a cold stick on the pan, which I then floured.

Healy’s instructions are easy, and the book is written in a way that made me feel he was standing over my shoulder, guiding me. “Faster! Keep beating,” I imagined him saying as I gingerly upped the speed of my mixer to halfway between the six and the seven. “Medium-high,” I heard him tell me, and I settled the lever on the seven. The butter and sugar mix was nearly white after five minutes of creaming. When I finished adding all the ingredients, I realized something was missing—missing from the butter, too. Salt. A sweet recipe that doesn’t call for salt is a terrible mistake, I thought.

And then I licked the whisk.

Five angels.

Oh, the last cake had a sweet batter, but the taste was artificial. This one tasted like the liquid version of my beloved white sheet cake.

Light and perfect, the batter went gently into the pan, and I smoothed it and resmoothed it, eating whatever extras were captured in the process, and the loaf went into the oven. Within ten minutes, the aroma filled the dining room, calling me.

Now, twenty minutes before the cake is to be checked (after about an hour and fifteen to twenty minutes), I decide to get started on The Cake Bible version. Rose Levy Beranbaum is a woman’s baker. Throw the wet ingredients together, throw the dry ingredients together, toss the in-between ingredients in, add some of the wet, add some more of the wet, add the rest. Voila! I don’t have to count mixing minutes or worry about temperatures (except for the eggs, which she likes at room temperature). And while I work, I hear the voice of my Jewish grandmother guiding me, only she isn’t saying, “Beat it faster.” She says to me, “Oy, you’re such a mess. This is how you live? Did you wear those shorts out?” She says, “You’re only going to have a taste of these cakes, right? You really don’t need it.” This is baking and guilt. This is home.

When the batter is ready, the angels gather round. Four of them sing. The fifth mouths the words. This isn’t quite as silky as the French version, but it is close, as is the color. I want to say that the flavor is nearly as outstanding. (Do I detect the most subtle hint of baking powder?)

It’s ten minutes early, but I open the oven door to put in the second cake and check on the first. It’s ruined. The top has browned. The sides have blackened. I turn it over on a plate, and a brick plunks out. (The angels walk out of the room, their arms folded across their chests.) If this were a State Fair, I would be out of the competition instantly, though the judges would still taste the cake. I have to know what might have been, too, so I slice an overbaked heel from the right end, put a less crusty portion in my mouth, then toss the rest in the sink. Despite the burn, it tastes like a sugar cookie. The interior of the cake is tender and finely crumbed but not moist. The flavor is light and fresh but not nearly sweet enough after all.

I watch Beranbaum’s cake like a hawk. Her instructions call for covering it with buttered foil after thirty minutes, which I do. Then, every five, I check it to see whether it’s done. My Jewish grandmother (whose name was also Ruth) tells me to keep checking it; she doesn’t trust my oven, either.

When it’s done, I compare the two cakes to each other and to what’s left of the first tube cake. I don’t want to feel as though the Healy cake has been given short shrift by the nasty brown crusts, but the French version does not compare. It shouldn’t, after all, get a thick, hard crust around it, should it? The first cake had no hint of a crust, just a golden color. The Beranbaum version, slightly crusty, tastes like a sugar cookie, too. It is fresh tasting, dense, and lightly sweet, though I still find it lacking in moisture.

Of the three, the first—with the recipe from the bottle of imitation extract—made the best-looking, moistest cake. I take some of today’s experiment to Ann and her husband. They are happy to oblige me but are not impressed with the results. Both liked the first cake best. My husband, Marty, thinks the flavors of the two loaf cakes are nearly identical; my daughter says they taste like pancakes without the syrup. Both agree that they aren’t sweet enough to remain frosting-less.

When next I make a pound cake—despite my extra pounds, it is soon—I alter the first recipe by amounts, include superfine sugar, exclude that icky-tasting extract. The result is what neighbor Val (a fine baker and cook herself) and friend Kim swear to be the best pound cake ever. I enter it in the Baltimore Book Fair's "Food For Thought" contest and think about what my life has become: cake and art.

The winner gets $250. That will just about pay for my cake party in October.

The recipe on the bottle of flavoring calls for shortening and margarine; I’ve already altered it by using all butter. (“It’ll be richer,” Susan Staehling told me earlier, her tone almost a warning.) Everything else—the six eggs, the three cups each of flour and sugar, and the cup of sweet milk—is by the book. (Sweet milk is whole milk. Susan once called the Superior company to check, and they told her the recipe was from a time when “women milked their own cows.”) The flavoring is added last, to the milk. It smells like an alcoholic version of candy corn—delicious. I am starting to regret my decision to make this cake. Maybe it won’t be as resistible as I expect.

The last thing I do is soak one of those Magi-Cake strips and pin it to the tube pan. (I probably shouldn’t reveal that I looked up pictures of tube pans on the Internet to make sure I was using the correct thing. I had always called them Bundt pans, not realizing Bundt is a brand.)

My daughter comes in from tree climbing and wants to know if it’s pound cake she smells in the oven. She spies the mixer attachment on a plate, and goes directly there to eat whatever batter is left. She assumes it is for her and doesn’t ask if she can eat it, though it is near dinner time. Her eyes roll back in her head, our household code for yummy.

And when it’s out of the oven, I can’t resist peeling off a piece where the cake has split, despite the Magi-Cake strip, though it is mighty flat. I am too impatient for a complete cool down and turn the cake over onto the lid of a plastic storage container. It’s far too pretty for plastic. I fish out my glass cake plate with the sterling silver base and reposition the fluted pound cake atop it, and then I take its portrait: my first cake as a—a cake book writer. My first pound cake. I pose it with a slice removed. I shoot the slice on a plate.

My neighbor, Ann, the cake decorator, is first on the tryout list. She looks at me, wide-eyed. “It’s so moist!” She says she’s tried dozens of recipes for pound cake and always comes out with cakes that are dry on the inside and crusty on the outside. I tell her about the butter-vanilla-nut extract from Cake Cottage, and she reaches behind some things to find her own bottle; she doesn’t remember seeing a cake recipe on it. I complain that the cake tastes a little artificial. Is it because I know the extract is imitation? Would real walnut and pure vanilla have made a difference? “Tastes good to me,” says Ann’s husband, Jim, in typical husband fashion.

Back at home, my own spouse declares the cake as moist and delicious as any other. But my daughter thinks it’s more desert than dessert and begs for ice cream. I want to tell her that she’s right, that cake without frosting might as well be bread. But I am too busy chewing a piece, nodding, my heart starting to beat just a little faster.

* * * *

According to the authorities on the subject—Rose Levy Beranbaum, author of The Cake Bible, and Bruce Healy, co-author of The Art of the Cake—I have made my pound cake all wrong. I said I had made this cake “by the book” with the exception of my use of butter, but I failed to mention that I softened it in the microwave. Berenbaum may not have a problem with that; her pound cakes, dubbed “perfect,” call for softened butter. But her recipes call for flour first, and she uses baking powder and far less milk. Healy would find neither recipe very French. His traditional quatres-quarts (named four-fourths because the original recipe called for equal parts flour, butter, sugar, and eggs), calls for everything at a specific temperature; the eggs, for instance, are at room temperature, while the butter is sliced and then creamed while still cold (unless your kitchen is cool), the superfine sugar chilled in the fridge. These two don’t even agree on what to use as a cake tester: Berenbaum suggests a wooden toothpick; Healy opts for a knife—a toothpick or cake tester is under-endowed with sufficient surface area to which wet batter can cling.

If nothing else, I am a person who can follow directions, so I use this skill to sponsor my own Pound Cake Bake Off, much to the delight of family and my many neighbors, all of whom seem to exhibit oodles more self-control than I.

The pound cake has been around since at least the 1700s. In 1796, Amelia Simmons (whose by-line includes “an American Orphan”) published this country’s first cookbook, entitled, American Cookery, or The Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables and The Best Modes of Making Pastes, Puffs, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from Imperial Plumb to Plain Cake, Adapted to This Country and All Grades of Life. In an edition published by William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1965, some of the original grammar is cleaned up a bit, though the author of the Foreword assures readers, “Enough errors remain to leave the proper flavor of the original. (Also note that the printer’s long f symbol of the time was used where we now use the curved s.) Her recipe for Pound Cake calls for:

One pound sugar, one pound butter, one pound cake flour, one pound or ten eggs, rofe-water one gill, spices to your tafte; watch it well, it will bake in a slow oven in 15 minutes.Another recipe, which she calls, “Another called Pound Cake,” says:

Work three quarters of a pound butter, one pound of good sugar, till very white, whip ten whites to a foam, add the yolks and beat together, add one spoon rofe-water, 2 of brandy, and put the whole to one and a quarter of a pound flour, if yet too soft add flour and bake slowly.

In more than two hundred years, the recipe has not changed much. Though we don’t measure in gills (about five ounces) or use rose water or, alas, brandy, a pound cake is a pound cake.

*****

Bruce Healy’s Quatre Quarts is in the oven. Despite my determination, my cautious preparedness, I am still a slob. The countertop has a light dusting of flour, egg drops have dried there, too, and everything near the stove is covered with a greasy film from a morning spent attempting to clarify my own butter. Both The Cake Bible and The Art of the Cake recommend clarified butter for the greasing of the cake pan; otherwise, the cake is likely to stick to the milk solids in regular butter. In economic terms, this means turning two sticks into one. I boiled the butter, skimmed the foam from the top, and strained the solids. Several times. Eventually, I wound up with a delightfully clear butter with which to coat the loaf pan (to keep the cake from sticking). I never got to use it. My loaf pans have a non-stick surface too slick to hold melted butter; it runs down the sides and pools on the bottom. I put the clarified butter in the fridge and rubbed a cold stick on the pan, which I then floured.

Healy’s instructions are easy, and the book is written in a way that made me feel he was standing over my shoulder, guiding me. “Faster! Keep beating,” I imagined him saying as I gingerly upped the speed of my mixer to halfway between the six and the seven. “Medium-high,” I heard him tell me, and I settled the lever on the seven. The butter and sugar mix was nearly white after five minutes of creaming. When I finished adding all the ingredients, I realized something was missing—missing from the butter, too. Salt. A sweet recipe that doesn’t call for salt is a terrible mistake, I thought.

And then I licked the whisk.

Five angels.

Oh, the last cake had a sweet batter, but the taste was artificial. This one tasted like the liquid version of my beloved white sheet cake.

Light and perfect, the batter went gently into the pan, and I smoothed it and resmoothed it, eating whatever extras were captured in the process, and the loaf went into the oven. Within ten minutes, the aroma filled the dining room, calling me.

Now, twenty minutes before the cake is to be checked (after about an hour and fifteen to twenty minutes), I decide to get started on The Cake Bible version. Rose Levy Beranbaum is a woman’s baker. Throw the wet ingredients together, throw the dry ingredients together, toss the in-between ingredients in, add some of the wet, add some more of the wet, add the rest. Voila! I don’t have to count mixing minutes or worry about temperatures (except for the eggs, which she likes at room temperature). And while I work, I hear the voice of my Jewish grandmother guiding me, only she isn’t saying, “Beat it faster.” She says to me, “Oy, you’re such a mess. This is how you live? Did you wear those shorts out?” She says, “You’re only going to have a taste of these cakes, right? You really don’t need it.” This is baking and guilt. This is home.

When the batter is ready, the angels gather round. Four of them sing. The fifth mouths the words. This isn’t quite as silky as the French version, but it is close, as is the color. I want to say that the flavor is nearly as outstanding. (Do I detect the most subtle hint of baking powder?)

It’s ten minutes early, but I open the oven door to put in the second cake and check on the first. It’s ruined. The top has browned. The sides have blackened. I turn it over on a plate, and a brick plunks out. (The angels walk out of the room, their arms folded across their chests.) If this were a State Fair, I would be out of the competition instantly, though the judges would still taste the cake. I have to know what might have been, too, so I slice an overbaked heel from the right end, put a less crusty portion in my mouth, then toss the rest in the sink. Despite the burn, it tastes like a sugar cookie. The interior of the cake is tender and finely crumbed but not moist. The flavor is light and fresh but not nearly sweet enough after all.

I watch Beranbaum’s cake like a hawk. Her instructions call for covering it with buttered foil after thirty minutes, which I do. Then, every five, I check it to see whether it’s done. My Jewish grandmother (whose name was also Ruth) tells me to keep checking it; she doesn’t trust my oven, either.

When it’s done, I compare the two cakes to each other and to what’s left of the first tube cake. I don’t want to feel as though the Healy cake has been given short shrift by the nasty brown crusts, but the French version does not compare. It shouldn’t, after all, get a thick, hard crust around it, should it? The first cake had no hint of a crust, just a golden color. The Beranbaum version, slightly crusty, tastes like a sugar cookie, too. It is fresh tasting, dense, and lightly sweet, though I still find it lacking in moisture.

Of the three, the first—with the recipe from the bottle of imitation extract—made the best-looking, moistest cake. I take some of today’s experiment to Ann and her husband. They are happy to oblige me but are not impressed with the results. Both liked the first cake best. My husband, Marty, thinks the flavors of the two loaf cakes are nearly identical; my daughter says they taste like pancakes without the syrup. Both agree that they aren’t sweet enough to remain frosting-less.

When next I make a pound cake—despite my extra pounds, it is soon—I alter the first recipe by amounts, include superfine sugar, exclude that icky-tasting extract. The result is what neighbor Val (a fine baker and cook herself) and friend Kim swear to be the best pound cake ever. I enter it in the Baltimore Book Fair's "Food For Thought" contest and think about what my life has become: cake and art.

The winner gets $250. That will just about pay for my cake party in October.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)